not a love story, but a story filled with love

By Crystal Perry, ASC -Journalism in the Digital Age- WDC 626, Spring 2020

“I’m going to jump out of this window,” he said in a calm voice. “Ok, but can you take a bite of this Peanut Butter and Jelly Sandwich first?” I asked. My husband, a 49-year-old black male, is experiencing low blood sugar. He is pacing the room wildly as I attempt to get him to eat. I question if this was what the pastor envisioned when he said: “for better or for worse.” I remember the pastor saying “Til Death due you part”…I watched as he paused. He touched his head and then he looked at me. “I do,” he said. That was almost 20 years ago. Eight years of life separates us, he is older. He throws the juice across the room. “In sickness and in health”… “Why do you have needles in your bathroom? I can’t be involved with drugs or drug addicts.” I recall our first conversation about diabetes and insulin dependency. Once a superstar athlete, he is now living a medical marvel. “Black men with juvenile diabetes don’t live to be 50 years old without experiencing some complications,” I recall the doctor’s statement. He takes a bite of the sandwich and finally drinks the pineapple juice. We wait. The sudden increase in glucose hits his system and he lies down to reset. I think back to the first time we met and watch the clock as he starts the transition back to his normal self. He smiles and says, “Thank you, you’re so pretty.” It’s in these moments that I hear my “I do” the loudest but then I realize that he did and he still does.

The dilemmas surrounding black love and marriage in 21st-century America are all too often mischaracterized as personal hardships that individuals must struggle to surmount. But, in fact, structural forces from racial slavery and terrorism, government welfare programs to mass incarceration, have forged the institutional basis for undermining black marriage. Black love exists and it exists in black marriage. But after twenty years in the “trap,” I think it’s important to focus on the things they don’t tell you. So rather than a love story, it’s stories filled with love that unmasks the monsters, highlights the asterisks and exposes all the invisible print of black marriage. As with any new adventure, I started writing about black love and immediately experienced those butterflies in your stomach. Do you know that feeling that you get when you think about your significant other? No? Think back to the start of the relationship. Ok! Are you with me now? Good.

I wanted to share my fairytale, as a black woman preparing to celebrate twenty years of matrimony to a black man and I wanted to list out the moments of breathtaking bliss. I wanted to give hope to those single black women searching for single black men. I wanted to inspire black married couples and hoped they’d see a glimpse of themselves and their spouse in my story. I was writing a love letter to black women about love and marriage when reality entered the storyline and I realized I was drafting a nightmare. I wanted to write a love story about black love and marriage but I kept coming back to Anita Baker and Gospels songs. If I’m honest, being a wife leaves me somewhere between “He’s Never Failed Me Yet,” by Cee Winans and Anita Baker Fairy Tales playing in my head, “I can remember stories, those things my mother said. She told me fairy tales before I went to bed. She spoke of happy endings, then tucked me in real tight. She turned my night light on, and kissed my face good night.” Did our mothers lie to us? The truth is, twenty years in a marriage can feel like twenty minutes and then some minutes can seem to last for years. Anita Baker Fairy Tales continues, “She never said that we would; curse, cry and scream and lie. She never said that maybe, someday he’d say goodbye. The story ends, as stories do. Reality steps into view. No longer living life in paradise-or fairy tales-uh.” Love, marriage, and relationships have never been easy, and in a 21st-century society in which relational commitments are increasingly attenuated, contingent, and impermanent, I sometimes question, does black marriage matter?

Love like faith is often defined by the individual or individuals experiencing it. Marriage as a system is similar, as society fills our head with fairy tales where the power of attraction seamlessly ends in happily ever after. But what of black love? Black love literally shouldn’t exist in America, in any form. Familial, heterosexual, trans, queer, community, basically any form of love involving black people. Everything was done to prevent it. Chattel slavery, as a defining condition of blacks in the Americas, made everything abnormal, including the institution of marriage, not least because slaves were not allowed to marry legally. Our historical legacy in American society saw black women raped, black men tortured, and black families ripped apart at auctions. Powerless and unable to protect our love or our loved ones. Black families were separated several times over, while marriage was forbidden and the structure of slavery in general was such that love, as well as many other ideologies, would not develop. Now, more than 400 years after the first slaves landed, in a society that still views skin color as a weapon, I argue that black love and black marriage remain revolutionary actions for black women in 21st-century society.

Black marriage, in its purest form, is a glaring example of black activism and resistance in America. The grim news about the state of Black heterosexual marriage can be found in headlines, almost daily, young women are presented with data about the lack of marriageable Black men, and statistical studies that routinely show Black marriages are difficult to maintain. Love and marriage, we are told, go together. They fit and work together like a “horse and carriage” says the songwriter. Beyond the material aspects of marriage, finding love has been linked to prolonging our lives, improving emotional stability, and increasing the opportunity for a more positive psychological state of mind. Marriage, in particular, has been a complicated concept in African American history. Loving another person in his or her brokenness is a beautiful description of what it means to be committed to another person for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, until death parts us. But, what happens when that love is covered in racism and historical systems of oppression, sexism, and classism that cultivate competition while attacking collaboration? Is the opportunity to love and be loved equally available to all? At present, the majority of black women in America are single by circumstance, not by choice, and the statistics are jarring. “In 2016 just under half or 48% of black women had never been married which is up from 44% in 2008 and 42.7% in 2005” according to a recent study on black demographics. But for those who do find love and have chosen marriage, what happens next isn’t the happily ever after promised in the fairy tales! Or is it? Love is a universal language that we all define in and on our own terms. When we add the extra ingredient of our blackness, love can take on a unique power that is shared through an ancestral lineage rich with traditions and customs that have been passed on through each generation, and shaped by our own views on life.

Many little girls are still raised to prepare for marriage. All of our chores are related to cleaning the home and caring for others. We love our fathers and study our mothers. We are trained to notice and take care of the needs and wants of others while often denying our own. Our grandmothers, mothers, aunts, sisters, and cousins serve as models and during our most impressionable years, we are saturated with fairy tales that include princesses that need to be saved and a long line of princes ready to save them. You lie helpless and he’ll find you. You are defenseless but he will protect you. You are without food and shelter, but he will provide. That’s the general theme when it comes to traditional love and marriage set in a patriarchal framework backed by capitalism. I learned early to look to love as an escape. Love promised to fix the heartbreak and hopelessness associated with poverty. Love promised to endure through infidelity and domestic abuse. Love remains when hopes and promises are burned up in the aches of drug addiction and domestic abuse. So when I found myself pregnant at 19 years old, I dismissed the negative voices and chose love which ultimately led to marriage.

Happy 19th Wedding Anniversary

Wedding Toast 19 Years

Til the next year

Black Love Wins…19 Years

19 Years in “The Trap”

Crystal Perry, 19th Wedding Anniversary

Craig was a knight. I was a damsel in denial but definitely in distress. Eight years separate our births. I was eighteen years old and off to college. He was a twenty-five-year-old college transfer visiting his cousin for the summer. Up until we met in the parking lot outside of a club in Decatur, GA we were strangers on separate paths. As destiny would have it, those paths become parallel and eventually intercepted and became one path. That’s the part of the fairy tale that remains unknown. The happily ever after is what you make of it. Far too often the love stories we’ve come to worship tell us how the relationship starts but never how to sustain it. Marriage isn’t simple. It’s messy, complicated, and full of unexpected surprises of every variety. It is also joyous and wonderful, but it’s not a fairy tale or a cliche. After 24 together, and 20 years of marriage, I can say that the fairy tales and cliches never come close.

“Piss or get off the pot.” That’s the phrase I used to alert my boyfriend that I was growing restless with dating. Our twin boys had just celebrated their first birthday and I was living with my mom and his mom while he was working in Denver. It was my Junior year in college and after taking a semester off for motherhood, I was back in class and on track to graduate in May 2000. Craig had been gone for over 6 months, coming home once a month on the weekend to visit. He had graduated and was promoted to a field position that offered more money and allowed him to travel and support his girlfriend, his two kids, and our moms. The situation worked but was less than ideal. After six months, I felt like I needed to see him so I made arrangements to travel by bus to Denver. It was a 24-hour bus ride. I would be in his presence 48 hours and then take another 24-hour bus ride back. Clearly, I was in love. Completely smitten and desperate to spend some quality time with the man I loved. There was no question that he would take responsibility for our care while I was in school but did that responsibility include a future past graduation? And if so, did that future include marriage? Craig and I had been exclusive for over 3 years and were now parents of two boys. I started the ride excited and looked forward to seeing and touching this man that I loved so deeply, but after about 8 hours I started to question if my actions made sense. Was I heading into a weekend of love or a potential break up? I took the time to reflect and journal and ultimately decided that when I saw him I would ask the hard question and clear the air. I had planned to ask, “are you going to marry me,” but before I knew it I looked at him and said, “piss or get off the pot.” It wasn’t sexy, but it did launch the engagement conversation.

Both my grandmothers were married. They both gave birth to children before the age of eighteen and those children had multiple fathers, but they were married nonetheless. I wish I could tell you that matrimony meant they were treated well and protected and lived a life of ease and comfort, but that description would be false knowing I am the descent of two black women from the deeply segregated south. The myth about marriage is that it creates a lifestyle or stability for women as we transition from our father’s homes to our husbands. Knowing the historical position of black women in American history, I knew and understood from my own experience and by observing the experiences of the black women in and around my community that marriage, especially to a black man, is a revolutionary choice. A choice often aligned with misfortune, discrimination, low wages, and high barriers. And, how does a woman endure years of what can only be described as mistreatment and abuse and categorize it as a happy and loving marriage? Fairy Tales and Happy Endings have never been on the menu for black women. Yet we are taught and seek to dine at the table of matrimony and shop at the bridal boutique. Becoming a wife, especially of a black male and raising black children in America, is a sign of status and a sacrificial accomplishment when you look at our history in the country. Black children are literal black wealth, historically and in the present day. Marriage, specifically in the black community, is a powerful creator and sustainer of human and social capital for adults as well as children. I would argue that black marriage is as important as education when it comes to promoting the health, wealth, and well-being of adults and communities. When black men and women are able to work together in unity, and love is born out of this unity, we are a powerful force. We have a better chance of changing the direction of our communities while having a positive impact on our children if we take a look at the facts. It is not in the best interest of those that oppress our people for us to work in unity. The media takes the exceptions and portrays them as the norm, and we accept it as truth. Over 80% of black men that are married are married to black women. Over 90% of black women that are married are married to black men. Nonetheless, black women are often demeaned and degraded by data suggesting we are doomed for a life.

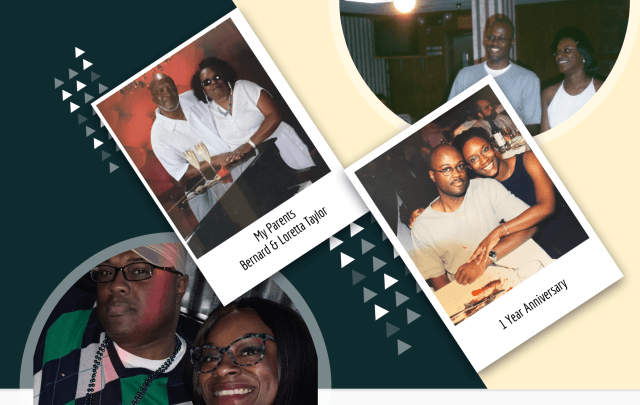

My parents modeled all the ills of matrimony from misuse of funds, to drug abuse, domestic abuse, infidelity, and absenteeism but remained committed for 38 years until my father’s passing left my mother a widow, March 21, 2019. The youngest of three girls, but sixth in a sibling group of eight, she speaks of her relationship with my father now through rose-colored memories dismissing the violent dysfunction that was my childhood. By the time I came along both sets of my grandparents had settled into family life, so although I’ve heard the stories of alcoholism, infidelity, and run-ins with law enforcement, I never witnessed my grandparents behaving in a demeaning or derogatory manner. Both sets of grandparents managed large families. My parents are both one of eight children. All but one of my female role models were married growing up. I never acknowledged or celebrated my parents’ marriage growing up. I was the dark-skinned, nappy-headed bastard child, born out of wedlock two years before my parents even began to think about marriage. Though my mother refuses to confirm what she describes as feminist conspiracy, I’d heard that when my mother became pregnant with my brother, then my paternal grandfather demanded my father be responsible and honor my mother now that she was pregnant with a boy.

My mother met my father when she was sixteen years old, “we were across the railroad tracks,” my mother always talks about her meeting my father for the first time as if she were describing the scene in a forbidden love story, it’s as if she were Juliet and he was Romeo. Her hands are soft though they sting with the aches and pains of arthritis. She has what some would call a lazy eye, she says that eye helps her “see people for who they are” and she believed in her heart that my father was a good man and that their love story was one for the history books. “One life, one wife,” is something my mother loves to repeat when telling stories about my father. You can see my mother smiling when she walks into the room although you will hear her first. “I’m here. I’m in y’alls house.” My mom is a loud person with a calming presence. She has big deep dimples in her cheeks which sing out we’re happy when she starts to laugh. My mother is a black woman with a medium skin tone, even at 64, she wears a stylish faded haircut and has committed to blue dye rather than natural grey. Though once petite and slender, her 5-foot height frame now balances her weight and health conditions. “I’ll never see him again. I’ll never experience that smile and wonderful personality.” She is a Christian woman who prides herself on being married to my father for 38 years. She is a caregiver and spends her time assisting seniors aging in place while living at home alone. She is a hugger and calls you to prayer on a phone call, virtually and in-person if she feels your spirit is uneasy. She is the mother of one daughter and two sons. She is twenty years sober for alcoholism and drug abuse. She is a widow and watching her grieve reminds me that true love transcends “til death do us part.” When I first told my Mom about Jessie and Faye she became teary-eyed. “That sounds like me and your dad,” she paused, “We got married and nobody knew about it.”

If you’ve ever watched a kid win a prize then you know exactly how he looked at her. Jessie, a 79-year black male, sat next to his wife Faye, a 79-year-old black woman. Jessie and Faye have been married 62 years and had six children together. According to Jessie, “he had his eye on Faye,” since “grade school.” He smiled when he spoke and would often pause to connect eyes with his wife as he responded to my questions. He corrected her when she seemed fuzzy on the details. And several times they both burst into laughter together. “A good husband,” – Jessie pauses for a moment. “A good husband wants his wife to believe he can do anything.” – Jessie. Faye smiles, “Well I guess that’s what’s kept us together because I thought he must know what he is doing” she paused, “Being married, you have to listen. Listen more than you talk. I was often quiet and not because I didn’t have freedom, I just figured he knew what he was doing and he didn’t stop me from what I wanted to do.” When I asked about their wedding day, Faye started to grin. She leaned back in her set almost making it appear as if Jessie had moved in closer.

Jessie started, “Well we talked about it. And I said, we were going to do that. (Meaning get married). And she kept asking me when.” Faye interjects, “I had already graduated because I attended first grade at 5 years old. He was still in school about to finish up.” Jessie continues, “she knew I had got my bus check for the month so she asked for a date.” We all laughed. “Back then it cost $13 to get married and my bus check was only $12 a month, so I went down one day early and paid $3.00, then the next day I paid the other ten.” Faye smiles, “I never knew how much it cost.” Jessie continues, “so I had just got my bus check for the month so after school, I picked her up and we went down to Dylan.” Faye opens her hand and says “just like that and we got married.” “Yeah, we got married and then went home to our separate houses.” He turns to Faye, “what was it one or two years before we told our parents?” When I asked about specifics on the wedding day, Faye replied, “Back then black folks didn’t have weddings. I think we were married some years before (named black bride and father) had a wedding.” Her daughter in law Angela chimes in, “I didn’t want a wedding they (looking over at her mother in law) had to talk me into it.”

I immediately start to think about my proposal and wedding day. “Renee, can I speak to you for a minute?” I was in the kitchen of our small two-bedroom apartment when I heard him call my name. He was home for the holidays and although the apartment was in our names, both his mother and my mother lived with us as they were, in theory, helping me with the twins while he worked in Denver to support the family. It was Christmas Eve 1999 and he and I were still in love and co-parenting under the official titles of boyfriend and girlfriend. The twins were two months away from two years old and had just mastered walking so there was a fence blocking the doorway preventing them from entering the kitchen. I remember stepping over that fence and glancing at the Christmas tree before heading back towards our bedroom. The door was open so I paused waiting for the voice to find me and call out to me again. “I’m in here.” There was a walk-in closet separating our bedroom and the master bathroom. I walked in the closet and there he was, already on one knee and holding a black box wrapped in velvet. I stood there silent, wishing the closet was cleaner. I focused on his knee that sat on a pile of unfolded laundry and his foot that rested in a sea of shoes. He started speaking, his voice was shaking and he seemed vulnerable as he promised to “love, protect, and provide.” He opened the box and presented me with a customized ring that he himself had designed. He asked and I said, “Yes.”

The 2,024-room New York-New York Hotel and Casino is an upper-middle-range themed property. The hotel sat at a great location on the southern end of the Las Vegas Strip. It was a replica of New York City and offered 30,000 square feet of meeting space, plus a staffed business center. We arrived in a taxi and immediately checked in after making it through the busy airport. We opened the door and we were greeted by a spacious room with an oversized TV and big windows. Outside I could hear the screams as the Roller coaster with a 180-degree twist and panoramic views whizzed by outside. This was my first time in Vegas and I was amazed by the size of the outdoor pool with loungers and cabanas as well as the fees for using said services. I walked wide-eyed through the medium-sized casino with dozens of gaming tables and 1,500 slots. The noise and sounds were overwhelming, multiple dining options, including a buffet restaurant, Shake Shack, and steakhouse, Dueling piano bar, adults-oriented risqué Cirque du Soleil performance, and an Irish pub. We walked through the main lobby which appeared to be a large arcade that has dozens of family-friendly machines, and many shops and we visited the small but pleasant spa, with a decent fitness center that offered soft sounds and natural light. My heart was pounding and he was holding my hand, “this is where you will come tomorrow morning for your makeover.”

The reception was a stark contrast to the week of bright lights and consistent sunlight found in Vegas. The room was dark and felt damp. The carpet was a dull dark green and the floors were uneven in certain spots. There is a noticeable dip when you walk through the doorway. The bar sat back in the corner. It was directly adjacent to the lifted platform that doubled as a stage. The room easily seats 75 people. There are 10 to 15 tables scattered throughout the dark, damp space. Each table has a set of matching chairs. The chairs were covered in polyester print that could have easily been wallpaper. The tables were wood and shined as if someone had recently polished them with oil. The walls were covered in striped fabric wallpaper with a repeating pattern of gold, green, red, and blue.

Twenty years later, conversations about getting married have shifted to arguments about how to stay and maintain the marriage. I grunt and completed a full circle while lying next to him. He doesn’t move. I tap his leg and say “I know you’re up. I need you to hold me.” He positions himself towards me and places one arm over me and the other underneath. He groans. Immediately I jumped up, “this is exactly what I’m talking about. How am I supposed to live like this?” He lies there quietly, still positioned as if he were holding me. “What? You said to hold you and I’m holding you?” I open and slam the door. “Why the hell are you doing all that groaning and moaning? I didn’t know holding your wife in bed was such a fucking chore!” He lies flat. His hands are open and laying on either side of him. I retreat to the bathroom. “Come back to bed,” he asks in a low but loving tone. “Bring your spoiled ass back in here, I was holding you” he whispers, now with irritation. He pauses. “How are you upset with me for doing what you asked?” His voice becomes deeper. “Not only do I have to hold you, but I also have to be completely silent,” you can hear the frustration in his voice. “Renee!” He says my name in a commanding tone. I open the bathroom door and appear at the foot of the bed. “Why do you have to be so mean?” I say sounding both exhausted and defeated. “Ok,” he says. “Come back to bed. Are you coming back to bed?” His tone is welcoming although I can hear him whispering “your crazy ass”. I walk around to my side of the bed and retreat under the covers. “Do it right,” I say as if they’ve made an agreement. He starts to laugh and says, “come on, can I breathe though”? We both giggle. “Just a little,” I replied. I adjust my pillows and he turns to position himself to spoon me, placing one arm over my body and the other underneath. Black love is full of joy and pain built not only in this generation but generations from long ago and for those of us who choose marriage and to stay married, black love and marriage is ours. What I’ve learned over twenty years is this. Black women in black marriages, we get to define its success, the same way our kinky hair is ours, our soulful walk is ours, our struggle is ours. There is a certain air of strength to black love, just as there is a specific power in black marriage. A hidden power within that can only be formed by persecution, ridicule, segregation, the history that the black man and the black woman have shared since we arrived in this country. We love hard. We fight hard. Black love is strength and therefore black marriage is the greatest demonstration of love.

That said, the stresses on Black marriages are best understood by looking at them through a prism that highlights the intersection of gender and race. The decision to marry someone of similar educational status is called assortative mating, and for black Americans, particularly black women, the ability to participate in such forms of marital selection is slimmer than they are for women of other races. For one, black women are much more likely than their male counterparts to obtain college degrees. They’re also less likely to marry outside of their race, which can leave them with fewer choices when it comes to matching up with someone of a similar educational status. And that can have a ripple effect that impacts not only current earnings but future economic mobility. But as the saying goes, anything worth having requires work and maintenance. Black marriage is no different. Black love endures. Black love commits. Black love stays through sacrifice. Black love is limitless. As marriage continues to be a major life goal for many adults in the United States. True black love in many ways is still very much defined by hitting this goal. Black marriage, defined as black men married to black women in 21st-century society proves this. It is a love that has been molded by adversity. It screams in the face of all opposition “Nothing is going to tear us apart ever again”